Hadoop MapReduce in Python vs. Hive: Finding Common Wikipedia Words

Big Data. Hadoop. MapReduce. Hive.

We hear these buzzwords all the time, but what do they actually mean? In this post, I’ll walk through the basics of Hadoop, MapReduce, and Hive through a simple example.

I’ve dealt with Hadoop and MapReduce at work in the context of analyzing patent text, so it seems natural to choose the classic use-case: counting word occurences. To that end, I’ll find the most common words in a dataset that contains lightly pre-processed introduction sections of Wikipedia articles.

The dataset comes from Emily Fox and Carlos Guestrin’s Clusering and Retrieval course in their Machine Learning Specialization on Coursera. They use it for teaching k-nearest neighbors and locality sensitive hashing, but it’s also a great, simple dataset for illustrating MapReduce code. I’ve taken a 25,000 row sample for this blog post.

Before I begin, I need to give a huge shoutout to the Udacity course Intro to Hadoop and MapReduce. I went through this course in the spring of 2016 when I was using Hadoop at work for the first time, and it delivers a fantastic introduction. Most importantly, Cloudera and Udacity provide access to a local distribution of Cloudera Hadoop, which I used months later to run all the code in this post.

Okay. Let’s take a quick look at the Wikipedia data to see what we’re dealing with.

import pandas as pd

people_wiki_sample = pd.read_csv('/users/nickbecker/Python_Projects/hadoop/blog_example/people_wiki_sample.csv')

people_wiki_sample.head()

| URI | name | text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Digby_Morrell> | Digby Morrell | digby morrell born 10 october 1979 is a former... |

| 1 | <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Alfred_J._Lewy> | Alfred J. Lewy | alfred j lewy aka sandy lewy graduated from un... |

| 2 | <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Harpdog_Brown> | Harpdog Brown | harpdog brown is a singer and harmonica player... |

| 3 | <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Franz_Rottensteiner> | Franz Rottensteiner | franz rottensteiner born in waidmannsfeld lowe... |

| 4 | <http://dbpedia.org/resource/G-Enka> | G-Enka | henry krvits born 30 december 1974 in tallinn ... |

people_wiki_sample['text'][0]

'digby morrell born 10 october 1979 is a former australian rules footballer who played with the kangaroos and carlton in the australian football league aflfrom western australia morrell played his early senior football for west perth his 44game senior career for the falcons spanned 19982000 and he was the clubs leading goalkicker in 2000 at the age of 21 morrell was recruited to the australian football league by the kangaroos football club with its third round selection in the 2001 afl rookie draft as a forward he twice kicked five goals during his time with the kangaroos the first was in a losing cause against sydney in 2002 and the other the following season in a drawn game against brisbaneafter the 2003 season morrell was traded along with david teague to the carlton football club in exchange for corey mckernan he played 32 games for the blues before being delisted at the end of 2005 he continued to play victorian football league vfl football with the northern bullants carltons vflaffiliate in 2006 and acted as playing assistant coach in 2007 in 2008 he shifted to the box hill hawks before retiring from playing at the end of the season from 2009 until 2013 morrell was the senior coach of the strathmore football club in the essendon district football league leading the club to the 2011 premier division premiership since 2014 he has coached the west coburg football club also in the edflhe currently teaches physical education at parade college in melbourne'

Now that we know what the data contains, it’s time to dive into MapReduce and Hive.

What is MapReduce?

MapReduce is a way of thinking about big data problems as collections of smaller subproblems.

For example, imagine I wanted to count how many times each word appears in one of Anton Chekov’s short stories. I’d probably loop through the text, creating a key in a dictionary for every word (as it appears) and adding 1 to it if the key already exists. This works because the text of the story can fit into my computer’s memory and I can parse one short story reasonably quickly.

But what if I wanted to get every Facebook user’s most commonly used words during a specific event (say a presidential debate)? Or what if I wanted to do the same thing for every book, like Google does? Since I can’t fit that much text in memory (and going sequentially with an iterator would be painfully slow), I need a new framework. MapReduce is the answer.

The key idea is that no one aspect of this task is dependent on any other part (until the very final stage of getting the total count). Every time a word appears, I’m increasing the count by 1 regardless of what is happening elsewhere.

If there were 320 million books in the world, you could imagine every person in the United States counting the word occurrence counts in a different book at the same time. After everyone is finished, I could then add their answers together to get the word counts for all the books. In other words, I mapped the big task to lot of smaller independent workers, and then I reduced the many map outputs into the single answer I wanted.

That’s all there is to it, except we have fewer workers to use. Let’s write MapReduce Python code.

MapReduce in Python

To count the number of words, I need a program to go through each line of the dataset, get the text variable for that row, and then print out every word with a 1 (representing 1 occurrence of the word). Here’s my code to do it (it’s pretty straightforward).

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

def mapper():

for line in sys.stdin:

data = line.strip().split(',')

if data[0] == 'URI':

continue

if len(data) != 3:

continue

text = data[2].split()

for word in text:

print "{0}\t{1}".format(word, 1)

if __name__ == "__main__":

mapper()

I also need a reducer. The reducer needs to calculate the total occurrences for each word from the sorted mapper output. Though this code is less straightforward than the mapper, I’m not going to walk through every line of it. At a high level, this code loops through the sorted mapper output and totals the count for each word in word_count. If the current word is different than the previous word, it prints out the value in word_count since that represents the total number of occurences of the previous word.

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys

def reducer():

word_count = 0

old_word = None

for line in sys.stdin:

data = line.strip().split("\t")

if len(data) != 2:

continue

current_word, value = data

if old_word and old_word != current_word:

print "{0}\t{1}".format(old_word, word_count)

word_count = 0

old_word = current_word

word_count += int(value)

if old_word != None:

print "{0}\t{1}".format(old_word, word_count)

if __name__ == "__main__":

reducer()

With these two programs, I can run a MapReduce job on Hadoop.

Hadoop

Hadoop is a distributed file storage and processing system. It handles all the dirty work in parallel MapReduce like distributing the data, sending the mapper programs to the workers, collecting the results, handling worker failures, and other tasks. It’s a key part of many production pipelines handling large quantities of data.

Loading the Data into HDFS

First, I need to put my data into the Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS). Since I don’t want my data floating around randomly, I’ll make a directory for it and move it there.

hadoop fs -mkdir blog_wiki_input

hadoop fs -put people_wiki_sample.csv blog_wiki_input

Running the Code

In general, I can run Map/Reduce Python code with the following:

hadoop jar /path/to/my/installation/of/hadoop/streaming/jar/hadoop-streaming*.jar

-mapper mapper.py -reducer reducer.py -file mapper.py -file reducer.py -input myinput_folder -output myoutput_folder

This is a mouthful. It’d be inconveneint to have to type this every time.

Fortunately, I can create an alias for the hadoop jar ... command to simplify things. I just need to put the following code in my ~/.bashrc file.

run_mapreduce() {

hadoop jar /path/to/my/installation/of/hadoop/streaming/jar/hadoop-streaming*.jar

-mapper $1 -reducer $2 -file $1 -file $2 -input $3 -output $4

}

alias hs=run_mapreduce

Now, I can run Map/Reduce programs with hs and four keywords (corresponding to the $ inputs in the alias function).

hs wiki_words_mapper.py wiki_words_reducer.py blog_wiki_input blog_wiki_output

Bringing the Data Back

I’ll get the reduced data from HDFS and put it back on my local machine.

hadoop fs -get blog_wiki_output/part-00000 blog_wiki_output.txt

Since I only had one output file, this worked. With multiple output files, I’d want to use the -getmerge command to combine them and then bring it to my local machine.

Anyway, now I can load the output in Python and see the most common words.

word_counts_df = pd.read_table('/users/nickbecker/Python_Projects/hadoop/blog_example/blog_wiki_output.txt',

sep = '\t', names = ['word', 'count'])

word_counts_df = (word_counts_df.sort_values(['count'], ascending = False).

reset_index(drop = True)

)

word_counts_df.head()

| word | count | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | the | 483141 |

| 1 | in | 279455 |

| 2 | and | 268477 |

| 3 | of | 262134 |

| 4 | a | 169765 |

No surprises here. The most common words are the articles, conjunctions and prepositions.

Counting Words with Hive

So we’ve got MapReduce down. What is Hive?

Hive is really two things: 1) a structured way of storing data in tables built on Hadoop; and 2) a language (HiveQL) to interact with the tables in a SQL-like manner. It’s super useful, because it allows me to write HiveQL (hive) queries that basically get turned into MapReduce code under the hood.

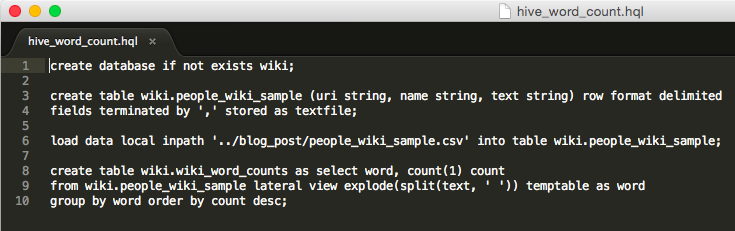

I’ll go through each line of hive code for the word count program on the interactive interpreter (signified by the hive> at the beginning of the line), and then show the hive script I used to do it all at once.

Creating a Database and Table

First, I need to create a database to put my hive table. I’ll call my database wiki, for obvious reasons.

hive> create database if not exists wiki;

Now I can create a hive table for the sample data.

hive> create table wiki.people_wiki_sample (uri string, name string, text string) row format delimited

fields terminated by ',' stored as textfile;

I can show the tables in my databases to verify that I created the table.

hive> use wiki; show tables;

OK

people_wiki_sample

Loading the Data into the Hive Table

With the table created, I can just load the data into it.

hive> load data local inpath '../blog_post/people_wiki_sample.csv' into table wiki.people_wiki_sample;

I can take a glance at the table from the interactive interpreter to make sure this worked. Since I’m “using” the wiki database, I don’t need the prefix now.

hive> select * from people_wiki_sample limit 2;

OK

URI name text

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Digby_Morrell> Digby Morrell digby morrell born 10 october 1979 is a former australian rules footballer who played with the kangaroos and carlton in the australian football league aflfrom western australia morrell played his early senior football for west perth his 44game senior career for the falcons spanned 19982000 and he was the clubs leading goalkicker in 2000 at the age of 21 morrell was recruited to the australian football league by the kangaroos football club with its third round selection in the 2001 afl rookie draft as a forward he twice kicked five goals during his time with the kangaroos the first was in a losing cause against sydney in 2002 and the other the following season in a drawn game against brisbaneafter the 2003 season morrell was traded along with david teague to the carlton football club in exchange for corey mckernan he played 32 games for the blues before being delisted at the end of 2005 he continued to play victorian football league vfl football with the northern bullants carltons vflaffiliate in 2006 and acted as playing assistant coach in 2007 in 2008 he shifted to the box hill hawks before retiring from playing at the end of the season from 2009 until 2013 morrell was the senior coach of the strathmore football club in the essendon district football league leading the club to the 2011 premier division premiership since 2014 he has coached the west coburg football club also in the edflhe currently teaches physical education at parade college in melbourne

Time taken: 0.087 seconds

Getting the Word Counts

With the data in the table, I can get the word counts pretty easily. I need to use three useful Hive commands: lateral view, explode and split. I’ll detail these three commands on their own to explain them and then execute the whole query.

So, what do these do?

According to the Apache wiki, “Lateral view is used in conjunction with user-defined table generating functions such as explode()”. I use lateral view to apply the explode function to the column text in every row in the table. Explode converts the text column to separate rows. Split returns an array with each word as an element (similar to Python).

So essentially, all I’m doing is creating a table, temptable, where every word in the text column gets its own row (just like in my mapper.py function). Let’s test it.

hive> select word from people_wiki_sample lateral view

explode(split(text, ' ')) temptable as word limit 10;

OK

text

digby

morrell

born

10

october

1979

is

a

former

Time taken: 6.441 seconds

Perfect, now all I want to do is group these results by each word and count the total rows for each word. Since I want to save the result, I’ll store it in a new hive table, wiki_word_counts.

hive> create table wiki.wiki_word_counts as select word, count(1) count

from people_wiki_sample lateral view explode(split(text, ' ')) temptable as word

group by word order by count desc;

After running this, I have a new table named wiki_word_counts in my database.

hive> show tables;

OK

people_wiki_sample

wiki_word_counts

I can look at a sample of the output, and clearly see it matches my Python MapReduce from above.

hive> select * from wiki_word_counts limit 5;

OK

the 483141

in 279455

and 268477

of 262134

a 169765

Time taken: 0.075 seconds

Bringing the Data Back Home

Now I can export this hive table to my local machine as a text file (or any file type) at my command line. Since, I’m running this from my regular command line (not in the one in the previous hive interpreter session), I need to tell hive which database to use.

hive -e 'select * from wiki.wiki_word_counts' > wiki_word_counts_hive.txt

Let’s see the output.

word_counts_hive = pd.read_table('/users/nickbecker/Python_Projects/hadoop/blog_example/wiki_word_counts_hive.txt',

sep = '\t', names = ['word', 'count'])

word_counts_hive.head()

| word | count | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | the | 483141 |

| 1 | in | 279455 |

| 2 | and | 268477 |

| 3 | of | 262134 |

| 4 | a | 169765 |

As we already know, it perfectly matches the previous code.

Using a Script to Manage Workflow

Using the interactive interpreter is fine (and useful for glancing at tables), but usually I want to build these into a production or analysis pipeline. For that, I want to wrap these commands into a script so they can be quickly run any time I want (such as to account for daily changes in the raw data).

At the command line, I can now type: hive -f hive_word_count.hql and it will run all of the code I ran interactively before. After that, I can just export the table in the same way.

With the output in Python on my local machine, I can just continue with my analysis. Maybe I want to compare the word distributions of these 25,000 Wikipedia introductions to another sample. Whatever I want to do with the output, by using a script to generate it I can easily re-run it or tweak it as the need arises.

Concluding Thoughts on MapReduce and Hive

Though I only dealt with counting words in this post, the MapReduce framework isn’t just limited to natural language domains. Even some machine learning algorithms can be turned into MapReduce problems (see this paper by Cheng-Tao Chu et. al for more information). If a data problem can be recast as a combination of the solutions to independent smaller subproblems, MapReduce may be able to help us get the answer faster.

Since we can write MapReduce code in many programming languages, why bother with Hive? To keep it brief: Abstraction saves coding time and mental bandwidth. Though many people spend time optimizing their code’s running time, fewer people spend time optimizing their code’s design and implementation time.

When I have to run some OLS regressions on panel data with entity-level fixed effects and clustered standard errors (you might be surprised how often I do this), I have a clear picture in my head of the R code I need to write to do that.

I don’t have to think about whether the normal equation or gradient descent is faster, whether I miscoded the gradient descent weights update, or whether I did the right adjustment for clustered standard errors. I don’t have to do any of that because I can use functions that take care of all this for me. By abstracting away from the details, I can get the output faster using less mental bandwidth.

To me, Hive is no different. I don’t need to waste time and bandwidth making sure the low-level details are correct every time I want to run a MapReduce job. Because of that, I can spend less time thinking about the implementation of the algorithm and more time thinking about the implications of the result.